Profile

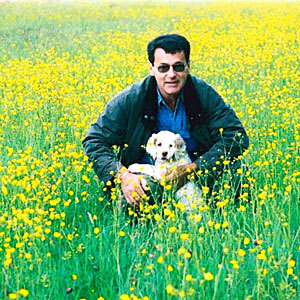

Since 1975, James has been the prime mover in the revival of Clumber spaniels as working gundogs – as advocate, writer, lecturer, breeder, trainer, shoot helper, gun and, in field trial competitions, handler and judge. He has gained field trial awards with many more Clumbers (ten) than any owner in the breed’s history. (more...)

Within the breed club (the Clumber Spaniel Club) in the early 1980s he arranged access for Clumbers to the BVA/GSDL hip scoring scheme, well before it was adopted by the Kennel Club, and endowed a research fund to offset the X-ray and submission fees faced by owners. Deeply concerned about large weight increases proposed by the Kennel Club in a revised breed standard (adopted in 1986), in 1982 he commissioned a paper (more...) from the leading canine geneticist Dr Malcolm Willis, senior lecturer in animal breeding and genetics at Newcastle University, in which he shared James’s opposition to the changes proposed, predicted adverse consequences, and called for a weight reduction rather than any increase. The Kennel Club went ahead with the increase anyway.

He co-founded the Working Clumber Spaniel Society in 1984 and was the main architect of its principles, positioning, communications and financial strength.

It was born from a need to fulfil a wholly different vision of the breed’s needs from that of the breed club, which was (and remains) substantially dedicated to exhibiting the dogs at shows. Its registration by the Kennel Club was achieved in the face of obstacles from within that body, influenced by the opposition of the breed club.

As secretary for 12 years, he led numerous new initiatives, from the re-establishment of minority spaniel breeds field trials and the creation of the society’s unique Breeding Commendation Scheme and Working Ability Assessments, through various designs of tests, matches and training events, to a successful recruitment campaign making first use of the Kennel Club’s computerised database. By satisfying a request from HRH The Princess Royal for a work-bred puppy, and later gaining her agreement to become the society’s president, he was responsible for the restoration of the breed to royal patronage which it had enjoyed under the Prince Consort and Kings Edward VII and George V. He conceived, wrote and published the society’s acclaimed brochure.

James believes that public awareness and education are essential to the attainment of the society’s goals, and in 1991 he received a major public relations industry award (IPR Sword of Excellence) for the high profile and recognition achieved for the society and the understanding for its mission.

While not intent on confrontation with those opposing the society’s mission, or those representing its interests too feebly, he has shown himself unafraid of controversy. He remains uncompromising in a commitment to further improvement of the Clumber spaniel as a sound and practical working gundog. Proud of the society’s record of real progress, he is upbeat about the breed’s future. With the dedicated support of his wife Christine (they married a month after taking on their first Clumber), James remains an active handler, working a team of up to five trained Clumbers on shoots, and an occasional breeder (more...) to maintain a pure working line now in its more than tenth generation.

From time to time James has enjoyed a change from Clumbers, and has trained, worked, trialled and bred cockers, gaining three field trial awards with a favourite bitch, and has trained and worked other breeds including English springer, German wirehaired pointer and large Munsterlander.

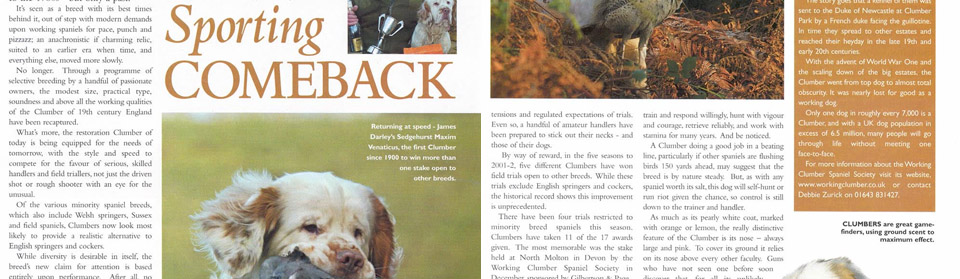

"Sporting Comeback", Sporting Gun, April 2003

"Sporting Comeback", Sporting Gun, April 2003 "Spaniels and the Stud Book", Country Illustrated,

November 2001

"Spaniels and the Stud Book", Country Illustrated,

November 2001 "The Clumber Spaniel, Heritage and Horizons", Gun Dog,

June 1996

"The Clumber Spaniel, Heritage and Horizons", Gun Dog,

June 1996 "Birthday bonus with Bella and Boris", Gundog Gazette (ezine)

"Birthday bonus with Bella and Boris", Gundog Gazette (ezine) "Under The Spell Of Spaniels", The Field,

October 2023

"Under The Spell Of Spaniels", The Field,

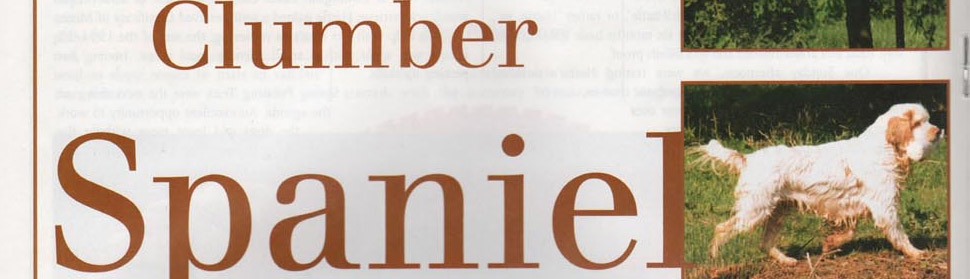

October 2023 "Return of the Clumber", David Tomlinson, Country Life cover story,

January 1991

"Return of the Clumber", David Tomlinson, Country Life cover story,

January 1991 "The sober-sided spaniels", Wilson Stephens, The Field,

January 1991

"The sober-sided spaniels", Wilson Stephens, The Field,

January 1991 "Major battle for minor breeds", David Tomlinson, Shooting

Times, July 2002

"Major battle for minor breeds", David Tomlinson, Shooting

Times, July 2002 "Kites and Clumbers", David Tomlinson, Shooting Times,

December 4, 2013

"Kites and Clumbers", David Tomlinson, Shooting Times,

December 4, 2013 "Clumbers take cover", David Tomlinson, The Field,

February 2014

"Clumbers take cover", David Tomlinson, The Field,

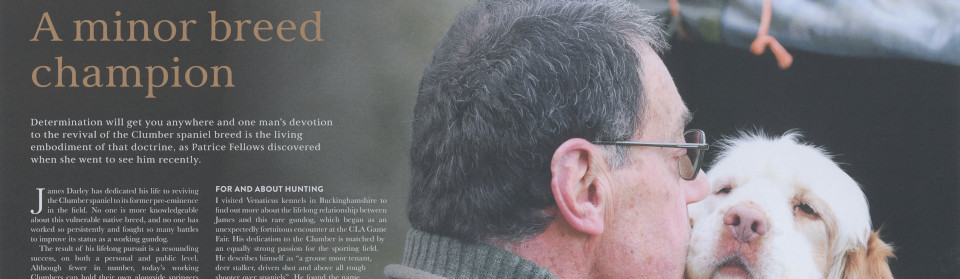

February 2014 "A Minor Breed Champion", Patrice Fellows, Gundog Journal Vol III(2)

"A Minor Breed Champion", Patrice Fellows, Gundog Journal Vol III(2)